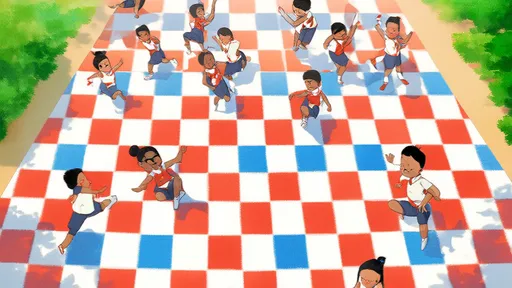

In the dimly lit studio, a dancer's body carves through space like a living brushstroke, while across the room, an artist's hand feverishly attempts to translate this ephemeral motion onto paper. This centuries-old dialogue between kinetic expression and static representation forms the core of our exploration into how the human body in motion becomes immortalized through line and form. The relationship between dance and drawing is not merely observational—it is a symbiotic conversation where one discipline breathes life into the other.

The Renaissance period witnessed the first conscious merging of these art forms, with Leonardo da Vinci’s anatomical studies of movement serving as seminal examples. His sketches of figures in motion revealed not just muscular mechanics but the very poetry of physical expression. Centuries later, Degas would capture ballet dancers mid-pirouette with pastels that seemed to tremble with residual energy, while Toulouse-Lautrec’s posters immortalized can-can dancers with lines that vibrated with rhythmic urgency. These artists understood that to draw dance was to chase a ghost—a beautiful, fleeting specter that could only be captured through the alchemy of artistic interpretation.

Contemporary visual artists continue this pursuit with increasingly innovative techniques. Some work with charcoal attached to long poles, allowing their entire body to participate in the translation of movement to mark-making—a physical echo of the dance they observe. Others employ time-lapse photography or sequential drawings that resemble musical notation more than traditional sketches. Digital artist Sabrina Ratté creates glitching video installations where dancers dissolve into pure line and light, questioning where the body ends and its artistic representation begins. These modern approaches demonstrate that the impulse to capture dance visually remains as vital today as it was in the Lascaux caves, where ancient artists first painted hunting rituals that blurred the line between documentation and choreography.

The dancer’s perspective reveals another dimension to this interdisciplinary exchange. Renowned choreographer Wayne McGregor frequently collaborates with visual artists during rehearsal processes, using their drawings as movement scores. Dancers might physically interpret a series of aggressive zigzags or embody the gentle curve of a charcoal smudge. This reverse translation—from line back to body—creates movement vocabulary that might never emerge from traditional choreographic methods. The drawn line becomes a movement prompt, a physical manifesto, and sometimes a brutal taskmaster demanding impossible contortions from the human form.

Perhaps the most fascinating development in this intersection is the emergence of real-time drawing technologies that allow artists to create digital illustrations projected behind dancers as they perform. These installations create feedback loops where the dancer responds to the evolving drawing, which in turn evolves in response to the dancer’s movements. This creates a third art form in the space between disciplines—a hybrid performance where neither dance nor drawing takes precedence, but together generate something entirely new. The body becomes both subject and co-author of the visual landscape, blurring the distinction between performer and creation.

The philosophical implications of capturing movement through static lines raises profound questions about time, memory, and embodiment. Every drawing of a dancer is inherently a lie—a frozen moment in an art form defined by its temporality. Yet this "lie" reveals deeper truths about weight, energy, and emotion that might escape even video documentation. The artist’s selective emphasis—whether exaggerating the extension of a limb or capturing the trembling tension in a suspended arabesque—functions as a kind of visual criticism, interpreting the dance through deliberate omission and amplification. These drawings become cultural memories of performances that otherwise disappear into the past, preserving not just the choreography but its emotional resonance.

In dance education, drawing serves as an unexpected but powerful tool. Students at the Paris Opera Ballet School have historically been taught to sketch choreographic patterns as part of their training, developing a spatial intelligence that transcends physical practice. Meanwhile, animation studios hire modern dancers not just as motion capture models but as collaborative storytellers who help artists understand how emotion manifests physically. This cross-pollination enriches both fields, proving that the line between these disciplines is not a barrier but a bridge.

The ongoing conversation between dance and drawing continues to evolve in surprising directions. Motion capture technology now translates dancers’ movements into complex digital wireframes that become raw material for both choreographic analysis and visual art. Augmented reality apps allow viewers to point their phones at drawings and watch them erupt into motion. These technological developments don’t replace the traditional relationship between the artist’s hand and the moving body—they expand its vocabulary, creating new dialects in this ancient conversation.

Ultimately, the attempt to capture dance through drawing is an act of profound respect—a acknowledgment that some moments of beauty are too precious to be surrendered entirely to memory. The resulting artworks stand as testaments to human creativity’s endless capacity for reinvention, proving that when two art forms engage in dialogue, they don’t just exchange techniques—they give birth to new ways of seeing. As long as bodies continue to move through space and hands continue to translate that motion into marks, this beautiful entanglement of disciplines will continue to evolve, reflecting our perpetual fascination with the poetry of the human form in motion.

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025